December 2019 - Market Commentary & Research

The Auto-Loan Market: Too Much Credit

In the summer of 2017, we published a piece highlighting growing concern in the auto-market; highly-levered purchases of automobiles and unsustainable lending practices. The piece was archetypal to the growing role of credit in society today, i.e. ever higher levels of debt across the board with no end to the growth in sight. The Wall Street Journal recently published a detailed article on the extent to which automobile financing has changed in the last ten years; most notably more aggressive financing options now available to consumers. Auto financing displays a principal issue of too much credit; expansive financing options can turn a well-intended push to make a good or service affordable to unaffordable, rather quickly.

Over the last ten years the aggregate dollar amount of auto-loans outstanding has risen considerably; helped by lower interest rates and continued collateralization by financiers. The growing use of credit to purchase vehicles personifies the paradox of our economy; the longest expansion in history, yet growth and purchasing power gains have been modest, and debt levels continue to rise.

Auto-loans offer a lucid example of how this dichotomy is playing out. As the WSJ article mentions: “U.S. consumers held a record $1.3 trillion of debt tied to their cars at the end of June, according to the Federal Reserve, up from about $740 billion a decade earlier.” Going further back in time, securitized vehicle loans were as low as $259 billion in 1992 (FRED).

Chart I, Source: WSJ

Principal to this growth in auto loans outstanding is the belief that that asset being acquired will continue to appreciate, or at least depreciate less than the expected loan balance at the time of trade in, yet new loans are increasingly including prior loan balances rolled into them. To quote the article, “A third of new-car buyers who trade in their cars roll debt from old vehicles into their new loans, according to car-shopping site Edmunds”. This is leading to the issue shown in Chart II, “underwater” vehicles. Unfortunately for car-owners most vehicles won’t, “re-appreciate” in value like homes can.

Chart II, Source: WSJ

This issue is not specific to auto-loans but representative of the broader use of credit (in unsustainable ways) to pay for major items. Student loans are the most politicized of this issue, but both student and auto loans highlight the issue of credit growth well in excess of the growth of the broader economy and purchasing power.

The growth in student loans is even more drastic and well understood. According to Experian, student loans have grown from approximately $650 billion in 2009 to $1.41 trillion in 2019 . According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 19.9 million students were enrolled in colleges and universities at the start of 2019. At this level of debt and with the current student population, this averages out to $70,351 of student loans per student. The average starting salary for a college graduate is around $51,000 (SHRM). This is a well repeated argument, but the intent here is to highlight how “making something affordable” via credit is having the exact opposite and possibly disastrous effect.

Finally, somewhat comically for the layman, the art market has experienced a similar problem (WSJ); excessive amounts of debt are being used for the latest art purchases. For the wealthiest, the expansive use of credit to purchase rare collectibles is making art difficult to afford.

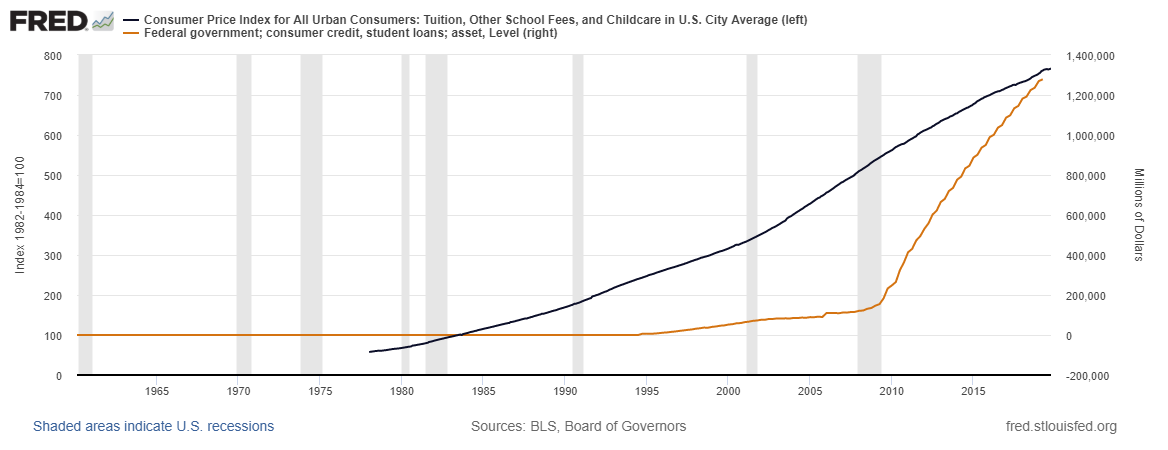

To contextualize the issue two final graphs are compared. The first displays the total Mortgage liability balance (black) and the Schiller Housing Price index (orange). The second displays the Consumer Price Index: Tuition, Other School Fees & Childcare in the U.S. (black) and Federal Student Loans owed to the Federal Government (orange). While the specific CPI referenced and Federal Student Loans are not as tight of corollaries as Mortgages & the housing price index, its not unreasonable to think a dramatic shake-out could occur with student loans and auto-loans.

Source: WSJ

Fundamentally, the genesis of the issue with last housing crisis (and other debt bubbles) could be phrased simply as; did a rise in housing prices create the need for more credit? Or did more easily available credit create higher housing prices? Avoiding a lengthy analysis into statistics and correlation, these simple questions point to what extent credit should be used for consumption, and how, if we’re honest with ourselves, how difficult it can be to understand the long-term consequences of decisions today.

There’s no easy or silver bullet answer to these questions. For the monetary economist much of this debate becomes relative, as long as the money supply is sufficient, pricing becomes irrelevant. On the opposite end, those concerned about sudden and destructive price inflation, the continuation of such credit growth could have serious negative consequences for the U.S. economy and U.S. dollar.

No one liked “holding the bag” when the roof collapsed on housing. Such a dramatic collapse is unlikely for student loans and auto-loans, but they will require increasingly complex remedies if such trends continue. Credit will always play a role for both of these markets, but let’s try and fix these issues before they come crashing down again. To put it in financial terms, the discounted cost to fix the likely fallout in the future is likely greater than the minor pain required today to correct the problem.