October 2019 - Market Research & Commentary

Less Productive Economies Headed for a Recession -

Anemic World Growth and Extreme Monetary Policy

Labor and capital productivity across the world have become a point of concern and contention since the financial crisis. Trapped in an expansionary cycle with lower than average growth, many have pointed to low productivity growth as a leading factor. Government and monetary leaders have supplemented low productivity growth with massive credit growth (and Europe is already restarting its QE program!) Unfortunately increasing the availability of credit can only do so much to spur economic growth and innovation. When investors are too risk averse they have engage in less risky and consequently less innovative ventures. Companies are without a doubt innovating, but that takes time and risk and even further time for those innovations to impact the commercial space.

As major economies such as Germany and Italy appear headed for recessions and lower growth in China is experienced (possibly a recession too, but that’s impossible to know from the government's statistics) productivity will have to be addressed as governments experience the limits of monetary and fiscal policy. Multiple theories and arguments have been posited to explain this trend, and these arguments have far reaching implications for the U.S. and the international economy. There is plenty of reason for optimism, as many technologies that might not be yet be impacting productivity data have the potential to generate meaningful productivity gains.

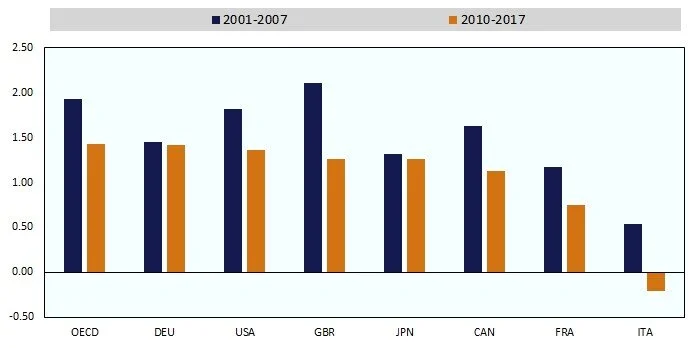

The OECD recently published a multi-year study on productivity across economic zones and countries, and the results are surprising. Across the G-7 productivity has trended downward, with a recent bump in 2018. For clarity, the OECD describes productivity “as a ratio of a volume measure of output to a volume measure of input use.” Most simply productivity grows by increasing the numerator (amount produced) or decreasing the numerator (using less inputs). Understanding the trends in productivity provides a layer of insight into the low growth and unprecedented use of monetary policy to generate growth in developed economies.

Chart I - Labor Productivity

Source: OECD

Chart II - Per Capita GDP Growth

Source: OECD

As Chart II shows, along with lower productivity growth, GDP per capita growth has come in at lower levels. This correlation is hardly surprising, yet despite being in the longest economic expansion, there seems to be little that can be done about the trend. A major driver is the change in employee demographics. Many skilled labor jobs are being replaced with automation causing more individuals to seek employment in service related fields, where increasing productivity faces natural human limits. One can only service so many accounts or customers at a time.

Turning to capital, on first glance though, the productivity gains from machinery (or capital) don’t appear to be paying off or making up to for the decrease in labor productivity (i.e. negative growth in capital productivity). But as some have argued whose arguments are explained further on in this article, issues with measurement and timing are likely culprits for seemingly very unproductive capital.

Chart III - Growth in Capital Productivity

Source: OECD

With these data points in mind, we’ve compiled a pointed list of explanations for the downward trend in productivity growth. Notably, the attempts to explain the lack of productivity growth aren’t united on the drivers, what to do about it, and if it is actually an issue to be concerned about. Ultimately these perspectives and arguments influence economic policy decisions and societies’s perception towards automation and open economies.

The Harvard Business Review’s explanation on the phenomenon is simply that enough time hasn’t passed for the full effects to show up in the data. For example, the article mentions how the greater use of computers in the 1980’s took another 7 years for its gains to have a meaningful impact on productivity statistics. This begs the question of how long is the waiting period? Or, when does the current wave of technological innovation, e.g. automation, reach a steady state so that one can gain a complete perspective on its effects? The current role of automation in the economy feels quite uncertain at this time. Much hype is generated surrounding automation’s potential, but for economists to fully appreciate the productivity gains, it might require an ex-post analysis.

From a historical perspective, arguing for the existence of a delayed impact is comparable to that of the industrial revolution in England. The timing and extent of productivity gains are widely disputed with some historians arguing wages more than doubled in the time span of 1780-1850, other historians argue that wage growth was only 30%. The difference is meaningful as increases in productivity should hopefully translate into more purchasing power for individuals. As this referenced Economist pieces explains, the discrepancy results from differences in measurement. This is an issue Robert Gordon, a professor at Northwestern University, sees as crucial to understanding productivity.

For Robert Gordon, better understanding productivity may come from reviewing the current methods of measuring productivity and updating them for the 21st Century. His analysis and review of U.S. productivity post-WWII suggests that the metrics are missing the mark when measuring productivity gains. Finally, the ways in which technology has advanced (e.g. smartphones) isn’t what is needed to improve productivity

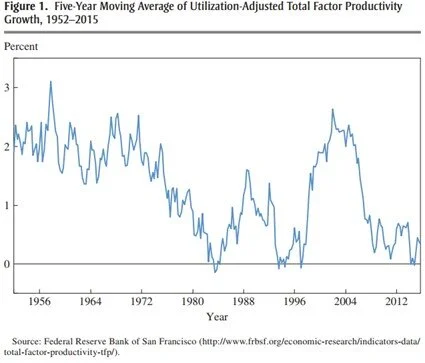

Gordon’s cites Chart IV, which shows the growth in Total Factor Productivity, or TFP, compiled from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. TFP is not the same as labor productivity but the two metrics speak to a similar concern, low productivity growth. As he points out, TFP saw a major spike in the late 90’s through the early 2000’s, and TFP has yet to grow anywhere near this level today.

Chart IV - Total Factor Productivity Growth (TFP) - 5 Year Moving Average

He concludes that mis-measurement has been the deciding factor in the productivity paradox. Most notably, he concludes the shift to the digital era, computers, smartphones, online storage, etc. was a one-time occurrence and productivity growth has now returned to a more normal level. Under such conditions, we should be looking for continuous gains to productivity but instead expect discrete, sporadic jumps that broadly change the workplace.

Finally, when combining the conclusions Gordon reaches with a recent article published by the Brooking’s Institute a better understanding of productivity comes about. The authors in this article analyzed the differing levels of productivity by metro areas in the U.S. They found that metro areas that have experienced the greatest share of technology based jobs have seen the most growth in labor productivity.

On the surface this conclusion feels obvious, but it reveals a key topic to analyze productivity further; demographic and broader economic trends. The disruptive force of technology has created major demographic shifts, which take time for its full effect to be felt. As people begin to move back to urban environments and more industries feel the effects of technology change, greater productivity growth will likely feed through the economy as a whole.

As the major global economies head for what looks to be another recession, increases in productivity are going to be crucial for bringing about another wave of growth. Synthesizing all of the innovations that are occurring around us, it’s clear that many of these; automation, artificial intelligence, 5G, etc. will lead to productivity gains in some way.

What’s not clear is how and exactly when they will come about, or if they can propel the economy to ever-higher heights. As a result, while the market may cheer (and rightly so) easy monetary policy to continue growth, its impacts can only be so great.